(6 February 1934 – 20 December 2021)

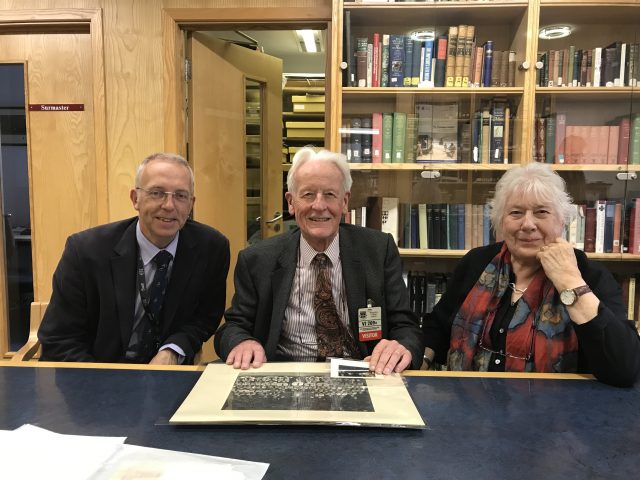

We have been informed by his wife Kathleen that Tony Bradley died peacefully at home with his family on December 20th 2021. Kathleen told us that Tony’s memories of his short time at MCS were vivid and formative. We send our condolences to Kathleen and Tony’s other family and friends. The photo above shows Tony (centre) with Kathleen (right) and MCS teacher David Bebbington (left) on a visit to the school in 2017.

The obituary below was printed in The Guardian on Tuesday 11 January 2022.

For a country without a written constitution, the UK was fortunate in having the authoritative and industrious Anthony Bradley among its leading constitutional experts. His work, spanning seven decades, shone a clear light on the sometimes ill-defined legal framework that underpins the modern state and expanded public scrutiny of government powers.

Bradley, who has died aged 87 of pulmonary fibrosis, was principal author of the standard textbook on constitutional law, served on the influential House of Lords constitution committee and taught a generation of judges at the universities of Edinburgh and Cambridge.

In his mid 70s, having embarked on a second career as a barrister, he presented arguments to the law lords on behalf of exiled Chagos Islanders who are still unable to return to their homes on the Indian Ocean archipelago.

One of his most innovative cases involved a courtroom battle in the early 90s against the home secretary, Kenneth Baker, over the deportation of a teacher to what was then Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) who was still pursuing an asylum claim in the UK.

The House of Lords eventually found that the home secretary and his officials were in contempt of court by unlawfully removing the teacher, establishing the principle that ministers are subject to court orders and enforcement proceedings can be brought against them.

The lawyer and former appeal court judge Stephen Sedley, who worked on early stages of the case with Bradley, described him as “a living resource with his compendious – though never flaunted – knowledge of constitutional and public law”, adding that “the quiet genius behind it all was Tony”.

One distinguished legal commentator, HWR Wade, described the judgment as the most important legal decision in 200 years.

Bradley’s international renown was such that he was involved in drafting new constitutions for Montenegro, Palestine and even the amalgamated trade union Unison. Liberal Democrat and pro-EU in political sympathies, his writings were nonetheless quoted widely in parliament by a range of MPs, including the Eurosceptic Bill Cash.

Anthony was born in Dover, Kent, where his parents, Olive (nee Bonsey) and David Bradley, ran a dyeing and dry-cleaning business. At Dover grammar school he was known as “Prof” due to his love of studying. He lived up to his nickname. After national service with the Royal Army Education Corps, Bradley won a scholarship to study law at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He graduated with a starred first in 1958.

Completing his training as a solicitor with the town clerk’s department in Reading, he secured another prize in his qualifying exams. Music was an abiding passion and it was at a Bach choir in Reading that he met Kathleen Bryce, a nurse who later became a health visitor. They married in 1959.

Bradley returned to Cambridge University the following year as a law lecturer, taking time out to help establish a law faculty at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. At the age of 34 he was appointed, in 1968, professor of constitutional and administrative law at Edinburgh University.

In 1965 he had begun editing Constitutional Law, a reference work first published in the 30s and already in its seventh edition. At Edinburgh in 1977, he relaunched it as Constitutional and Administrative Law; it became crucial reading for law students and is cited widely in UK court cases and foreign jurisdictions. Bradley continued working on updates until 2014.

Highly organised, Bradley was also known for his kindness and charm, and the encouragement he gave to others. His daughter, Charlotte, recalled Christmases during which foreign students who had no homes in the UK would share family festivities. He hosted parties and liked to play the viola. His musical tastes were not limited to the classical; he was a fan of the band Manfred Mann.

In 1989, he took early retirement from Edinburgh and joined Cloisters Chambers in London to train as a barrister; he was older than his pupil master. One of his first tasks was travelling around the country preparing compensation cases for women who had been sacked by the army when they became pregnant.

His academic background and ability to see both sides of an argument may not have been ideal preparation for partisan argument, which occasionally left him bemused at the discourtesy of opponents.

As well as fighting courtroom battles, Bradley gave expert evidence to parliamentary committees and commissions. One of his most important roles was as legal adviser between 2002 and 2005 to the House of Lords constitution committee, a body at the forefront of monitoring constitutional and legal developments.

He was the UK ’s nominee on the Venice Commission, an advisory body to the Council of Europe, which supports development of democratic constitutions and the rule of law.

Bradley was appointed an honorary QC in 2011. He continued giving lectures and writing articles for newspapers, including the Guardian. Among other roles, he was chair of Asylum Welcome, a charity that helps refugees in Oxfordshire.

In 2019 he welcomed the “clinical precision” of the supreme court ruling, in the case brought by Gina Miller and his former student Joanna Cherry, which found that Boris Johnson acted unlawfully in proroguing parliament.

Kathleen, their four children, Richard, Elizabeth, Lucy and Charlotte, and six grandchildren survive him.

MCS ranks among the top independent secondary schools, and in 2024 was awarded Independent School of the Year for our contribution to social mobility.

MCS ranks among the top independent secondary schools, and in 2024 was awarded Independent School of the Year for our contribution to social mobility.

28 of our pupils achieved 10 or more 8 or 9 grades in 2024.

28 of our pupils achieved 10 or more 8 or 9 grades in 2024.

In 2023-24, MCS received over £448,000 in donated funds.

In 2023-24, MCS received over £448,000 in donated funds.